Our firm has several defining pieces of corporate wisdom. They speak to the heart of our business and what we must do to be successful. One of them states:

“Eighty percent of solving a problem is defining it correctly.”

A colleague puts it a little differently: “Solving a problem is not the challenge; it’s defining the problem you’re trying to solve.” Here’s an example.

| Leadership Tool: All businesses face tough challenges at one point or another – a drop in sales, an increase in costs, a change in competition. Leaders can brainstorm effective approaches to solving these kinds of difficult issues by using this issue mapping tool. It may be used in conjunction with “A Method of Solving Tough Business Problems.” |

Our firm was hired to help public television managers sort through the thorny issue of “commercialism” in public television.

These 180 senior executives faced a dilemma: On the one hand, federal funding was declining, which meant stations needed to find new sources of revenue; on the other hand, viewers were accustomed to commercial-free fare. Selling commercial time was a risky way to get more money if it meant alienating viewers.

In this study, the same programs were aired in comparable markets with and without commercials. After two years, the data showed no significant drop-off in membership support (the money pledged by viewers). Nor was there a detectable decline in ratings (the number of viewers) in markets that ran the commercials. And advertising revenues did increase significantly, especially in larger markets.

First, they contended, the study only lasted a year, and therefore neglected any long-term effects–of which, they argued, there could be many. Second, they argued that markets of the same population size weren’t actually comparable. Viewers in New Orleans might not be comparable to those in Kansas City. Too many variables were involved to let such important policy decisions be dictated by this one study.

As we conducted our research, we saw a familiar pattern: Public television executives often clumped many issues into one – and then reacted in frustration at their failure to resolve the issue.

For example, what they branded “commercialism” was really a host of issues: worries about further loss of federal revenues, debates about the types of advertising that were acceptable, debates about appropriate length of commercials and the time slots when they aired, and the lack of consistency in guidelines from market to market, and show to show.

This phenomenon – lumping many issues into one seemingly intractable one – was not new to us. Yet before any solutions could be reached, these public TV executives needed a way to unravel these issues and determine their relationship to each other.

In essence, they needed to learn how to frame issues, much as a doctor needs to know how to isolate the cause of a disease.

Framing issues in effective ways is the subject of this blog. It’s analogous to what mathematicians do when they search for factors. Take the number 851. On its face, it appears to be divisible by only itself and 1. But it has factors of 23 and 37. Similarly, when we tackle a tough business problem, we need to make sure we’ve identified all the underlying issues before we begin trying to solve it. Otherwise, communication is going to get stuck – and result in a lot of frustration for everyone.

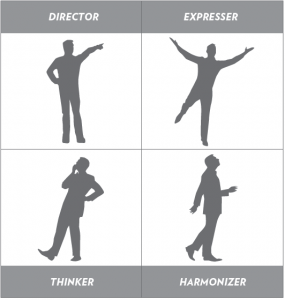

Thinkers will naturally understand the need to reduce an issue to its constituent parts. Expressers will cotton to this work as long as they perceive it as requiring creative input – which it does (as we’ll see in a moment). And Harmonizers will yearn to do what’s best to ensure a positive outcome for the group. But Directors will be impatient with this exercise – and push the group to get on with it – thereby jeopardizing the outcome.

This blog distills this process down to five steps.

Step one simply involves getting the group to tentatively define the problem it seeks to solve. It’s not important at this stage that everyone agree. The goal is to get the various definitions on the table. Maybe it’s getting profitability back on track. Or whether to run commercials. Or finding ways to cut costs. The way the problem is defined will change. But everyone needs to be on record stating: “This is the problem I think we’re trying to solve.”

State it this way:

“Eighty percent of solving a problem is defining it accurately. Therefore, the time we spend together in defining the problem we’re trying to solve is not a preamble to the work we have to do. It is the work we have to do.”

Kick it off by going around the room and checking with every member of the group. Ask:

“How would you define the problem we’re trying to solve right now?”

Tell the group that the issue will probably change as the conversation gets richer. But for now, it’s important that every voice is heard. If you’re not sure people have had enough time, ask them to think about it for a few minutes and write it down on paper. Or break into groups and have each sub-group talk about it and then report back. (This latter method actually reduces the time it takes to get everyone’s response.)

A Connecticut company, Jensen, Inc., makes high-quality sailboats. A strategic retreat of their management team is taking place at a resort in New Hampshire. For the first hour, the group discusses its communication styles and the tools of straight talk. Then someone says:

“Let’s identify the major strategic issue we’re trying to solve today. Why don’t we each define it as best we can?”

Sally, the marketing director, speaks up. “We need to figure out how to segment our customers more effectively. Which customers, in particular, do we want to reach in the next three years? With which products? Do we want customers who have purchased from us before, since they’re familiar with the Jensen brand and more likely to buy? Or do we want new customers whose income exceeds $250,000? Because they’re more likely to buy a new, more expensive and profitable model?”

The next person to take a stab at it is Sherry, the head of information systems. “We don’t have a database that tells us accurately who’s most likely to purchase, nor do we have demographic data. So one problem is defining what information to collect about our customers. Sally suggests some criteria. But maybe there are others that are more apt to lead to increased profits.”

“Like what?” Mike, the president, asks.

“Like whether they already own a boat, or whether they recently took out life insurance, or whether they eat out five times a week. I don’t know, it’s just that I’m uncomfortable with Sally’s analysis. It seems somewhat arbitrary to me.”

Mike takes his turn next. “I think Sherry is onto something else. She’s saying we need to decide what information we need before we can solve this problem. That gives me something to think about.”

“Can you state what you see as the issue before us today, Mike?”

“Yeah, more profits,” he says. “That’s the bottom line.”

In step two, the goal is to redefine the problem to everyone’s satisfaction. Everyone needs to discuss the issues related to the problem as it’s been tentatively defined. A likely outcome is that the definition of the problem will change – perhaps several times. That’s perfectly fine. The purpose of this discussion is to test whether there are other, more primary problems that should be dealt with first.

The wording of the issue, at this point, is not important. It’s just a starting point. Begin with your tentative definition of the problem. Then let people talk about related issues. Tell the group that this is the time to raise any and all related points. Explain that you’re all trying to put together a puzzle, but you need all the pieces before you can start. Tell them to make sure all underlying issues are allowed to surface. Say:

“This is a time when there are really no bad ideas. Let loose your creativity. Bring up your undiscussibles. Tell us what’s going on in your inner script.”

Someone may ask: What exactly are we trying to do? Answer it this way: “For now, we want to identify all the issues whose resolution would help resolve this question. We’re not concerned with their relationship. Just with the issues that are interconnected with this one. Ultimately, our goal is to define the primary issues that must be dealt with first as crisply and clearly as we can.”

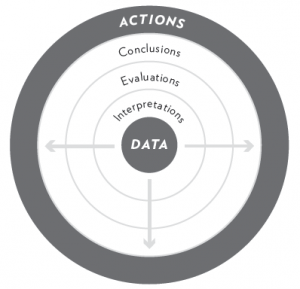

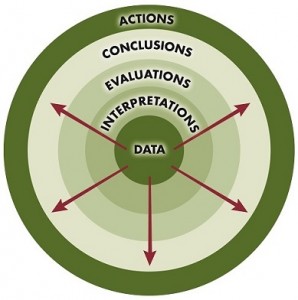

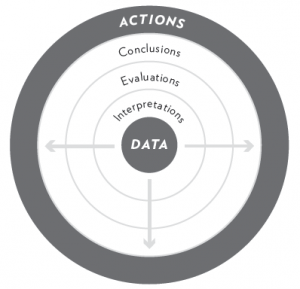

A word of warning: People will naturally shoot toward the outer ring of the Circle of Assumptions. So it’s common for a conversation on “what is the issue?” to veer off into “how do we solve the problem?” Before you know it, the group will be off like pack of wild horses into a discussion of the merits of a particular suggestion. Caution the group in advance to stay focused on defining the problem. Say: “We don’t want to talk about solutions just yet. Keep those thoughts to yourself for now.”

If people are reluctant to get going, it’s a simple matter to say:

“We need everyone to contribute their thoughts. The wackiest suggestion can sometimes lead to the most productive insight. So don’t edit yourselves. Let’s go around the room and each person will say what they think.”

And then proceed to do so.

On a flipchart, someone writes down Mike’s tentative definition of the issue: “Profits not high enough.”

Sally, the marketing director, says: “I guess a related issue is whether both our fixed and variable costs are under control. For example, our building is not very energy efficient. I’ve often wondered whether we could save money by making changes in the way it’s insulated.”

So on the flipchart, you write down: “Controls on costs e.g. heating costs”

Sherry, the information systems manager, says: “A related issue is profit margins versus earnings. Profit margins in our industry average around 8 percent. We’re at 8 percent. So are we talking about higher profit margins, or increasing our revenues at the same ratio to our costs and thereby increasing our earnings instead?”

So you write down: “Profit margins vs. earnings.”

Mike, the president, says: “A third way of looking at it is that we, as a company, don’t really have a clear picture of success. We like to hit our financial goals, we like to build good solid boats, but we don’t have other ways of defining success. Maybe that’s the issue.”

You write down: “Lack of measures of success.”

The conversation continues in this vein for about an hour until the issues fill three flip chart pages. At that point, you ask everyone to change gears.

When a scientist inquires into the causes of things, he pursues two separate types of knowledge: function and form. Function concerns itself with the purpose of something, its relationship to other elements; form concerns itself with how each element is made – its materials, its origins, its shape and size.

Function has to do with how various elements interact; form with how those pieces are constructed.

They are inquiring into the causes of things. They are not primarily interested in form, but in function, in the dynamics of the system and how to change it for the better. They are interested in influencing future events.

You can describe it this way:

“In the next step, we’re going to analyze the relationships of each issue on this list. Some issues are dependent upon others. Our goal is to find the primary issues, whose resolution is required before we can successfully tackle others. Let’s see if we can reach agreement on this relationship. In the process, we may generate new items for our list – and that’s okay. So let’s begin discussing the relationship of each item on this list.”

Someone will ask: “But some of these issues we can control, like the quality of our sails, and some are beyond our means to control or influence, such as changes in household income. It seems odd to include them all here.”

Tell them: “That’s a good point, and the next step in the process is to decide which of these factors we can control, and which we cannot. If you want to do both steps simultaneously, we can. But I prefer we not. Let’s just talk about their relationship.”

The Mind Map1 format (see example below) works best for several reasons:

A disadvantage is that it’s difficult to read words going in different directions across a page. But that’s a relatively small price to pay, given the advantages.

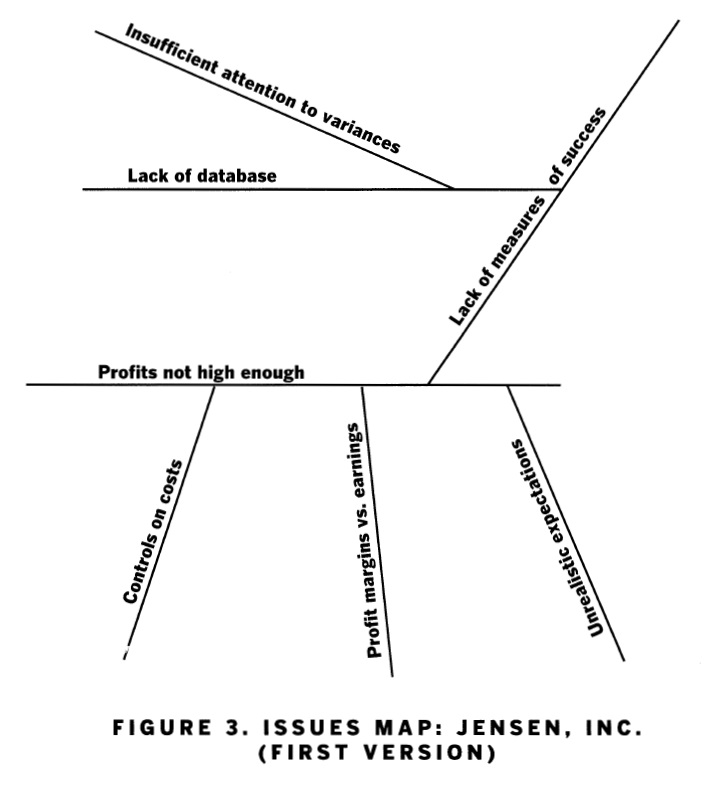

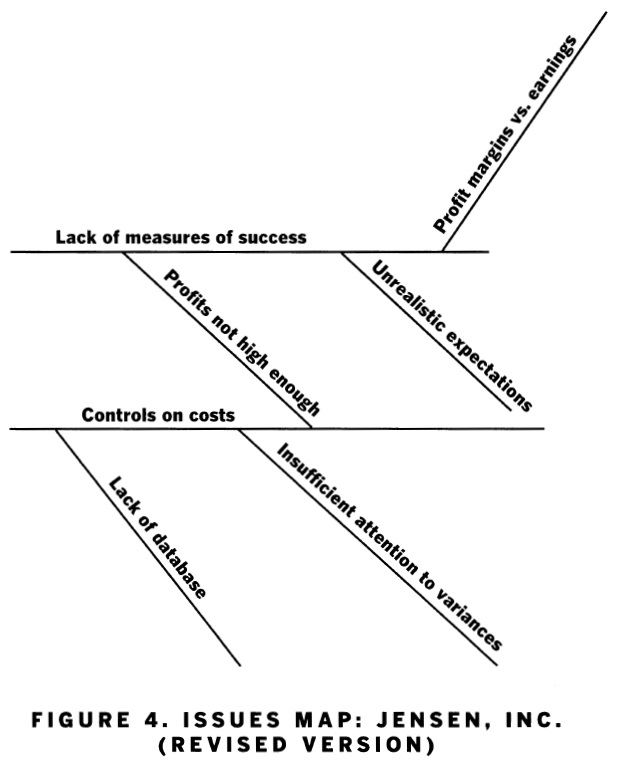

The list of issues generated in Step 2 looks like this:

| Related Issues • Profits not high enough • Controls on costs e.g. heating costs • Profit margins vs. earnings • Lack of measures of success • Lack of database • Unrealistic expectations • Insufficient attention to monthly variances |

After passing out blank pieces of paper to everyone, you say, “Let’s take these issues and map their relationships, with the primary issues at the center, and other issues branching off.”

Once the group begins, there’s spirited discussion about what belongs where. Everyone agrees that “Profits not high enough” is at the center.

Their work results in the following diagram:

Then Sherry speaks up: “I’m seeing ‘lack of measures of success’ as more primary than ‘profits not high enough.’ It seems to me if we had clear measures of success, that would change how we perceive our profits. So it’s more primary.”

Other people are asked their perspectives.

“I think she’s right,” Mike says. “It’s more central because it affects how we see our performance everywhere.”

“I’d also shift the one that says ‘insufficient attention to monthly variances’ so that it ties into ‘lack of controls on costs,’’’ Sally says. “It doesn’t affect the database. But it certainly affects our ability to control costs.”

“Everyone agree?” Heads nod.

“Okay.” You draw a second chart.

“Now that we’ve gone through this exercise,” you say, “take a moment and write down the issue you feel is most pivotal. We all came here today to help your company. So tell us what problem the company most needs to solve? Another way of looking at it is this…”

“What question, if answered, would result in the most benefit for thecompany?”

People take about three minutes for this exercise. When they report back, the decision is unanimous: They want to create a set of measurable benchmarks that define success. Each person is asked to explain briefly why this would have the greatest benefit.

“We’re too wishy-washy,” says Sally. “We need standards we can measure ourselves by.”

“Plus,” says Sherry “it would help if we didn’t simply accept the industry standard. Maybe our expected profit margins are putting a crimp in our growth. We should look at that.”

“As for me,” says Mike, “this is not the issue I would have thought to raise right now, given how I was seeing our short-term problems. But I see that it’s a very important conversation for us to have. It would enable us to play by a common set of rules, shoot for the same goals, and define winning in ways that we all understood. That would bring more focus to what we’re doing.”

In this case, the definition of the problem took only a couple of hours. But it can take a day, or even more.

It’s up to the people involved. If everyone feels they’ve pinpointed the issue that will yield the most benefits, then you’re done. If there are two or three major camps, then you’ve got to probe further. Ask each camp to explain its reasoning.

Follow the ground rules, give people a chance to test their assumptions, probe for the missing data, and reach agreements. Again, given the 80% rule, you cannot spend too much time on this part of the process.

Two different groups might diagram the issues here differently. There is artistry and interpretation involved. But still, the exercise is invaluable. It illustrates the relationships between issues. It enables a group to appreciate which problems warrant their attention first. And most important, it allows the communication to become highly focused and organized.

Miniature Toys, a maker of replicas of old-fashioned tin toys, had decided it needed to re-examine its sales strategy. It asked us to facilitate a meeting of the management team. After laying out the principles of straight talk, we began helping them define the issue.

“I see us needing to develop a new sales channel through direct mail,” said Bill, the sales director. “We’re getting chewed up on our discounts to retailers. We should capture 100 percent of our list price, not 40 percent.”

“But the problem is we need additional sales right now,” said Mary, the marketing director. “We should test direct mail, but I wouldn’t want to count on it when retail outlets are our bread and butter. They’re going to be hopping mad if we start selling direct.”

“I agree with Mary,” said Steve, her husband and the company’s CEO. He was nearing retirement and starting to let Mary run the show. “We’ve got to balance short term and long term strategies. Focusing on direct mail means a complete reorganization of how we do business.”

“When I think about it, I wonder whether the problem isn’t the expense side of our sales,” said Adam, the young CFO. “That leads to some unpleasant thoughts, but I wonder whether we can continue to sustain overhead that puts our break-even at 60,000 units per year. All those salespeople cost money.”

“I agree,” said Bill, the director of sales. “We need to grow in a way that simultaneously lowers our costs of sales and raises sales revenues. Direct mail is the answer.”

“How can we define this problem in a way everyone accepts?” we asked.

“One perspective, represented by Bill, says that direct mail would be a better route to long-term profits. Another perspective, stated by Mary and Steve, says that short-term profits will be jeopardized by a change from the current retail strategy. Does everyone agree?”

No one said anything.

“How far out in the Circle of Assumptions are these two points of view?” we asked.

“Pretty far,” someone ventured.

“Then maybe we should hold off accepting those perspectives,” we said. “Let’s just continue to explore the issue. The question is the long-term sales strategy. What are the related issues?

“I think we have a problem understanding how our business actually works,” said Mary. “Bill says direct mail is the way to go, and yet I don’t see it that way. If two smart people can disagree on something so fundamental, I wonder whether we really understand our business.”

“All right, so let’s reframe the issue: You lack knowledge about what drives your business. Let’s look now at what some related issues are. We need to test whether we’ve defined the issue crisply enough.”

“Well,” said Steve, “we have two sets of customers – our retail outlets and the people who ultimately buy our toys at the store. We know a lot about the former, and not much about the latter. It’s sort of an information gap. So we can’t help our retail partners figure out how to reach the customers most likely to buy our products.”

Good, we said. So what’s the issue?

“We can’t provide good marketing information to our retail stores. So we’re vulnerable on two fronts: to low-ball wheeler-dealers and to competitors who know our customers better than we do.”

The conversation proceeded along these lines for another 45 minutes.

Ultimately, the group decided the core issue was the company’s inability to be an information company in an information age.

The conversation focused on developing a strategy that could continuously generate information about customers, which in turn would create leads to additional sales.

Customers that could help Miniature Toys fulfill that strategy would be considered priority customers and given special treatment, with such things as a more expensively produced catalog, first priority on rare or close-out items, and a Christmas bonus program. Those that could not would be relegated to a second tier.

The initial problem – “generating long-term profits” – was redefined as “becoming an information-based company.” Once the group agreed on the problem, the solution lay within reach.

Typically, the issues will fall into two categories: those within the group’s control and those outside its control. It is self-evident that you cannot control the latter. Therefore, the group should focus on issues it can control.

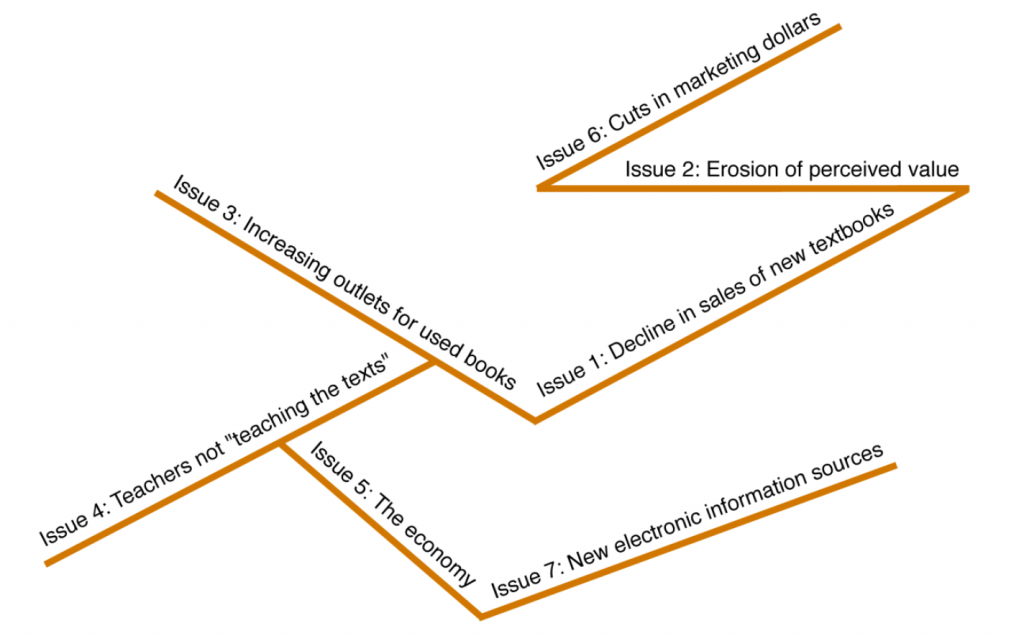

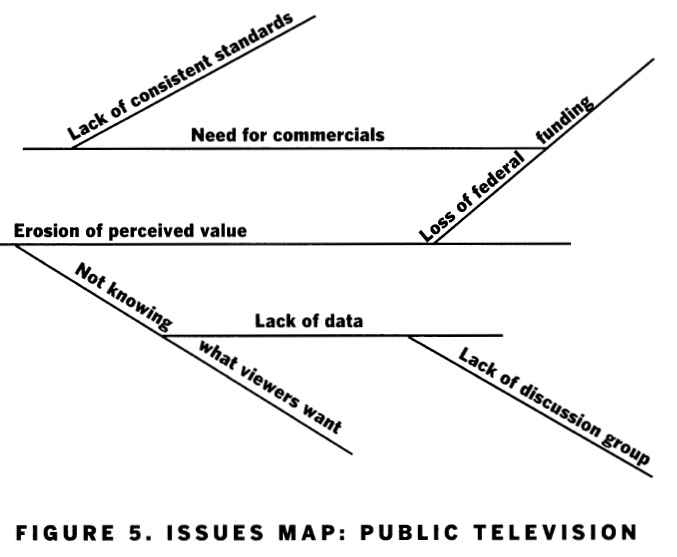

For example, take the diagram of issues related to commercialism in public television (see chart). Which of these issues should station CEOs focus on?

Someone says: “We can’t directly control the level of federal funding. That’s for Congress to decide.” So the issue gets crossed out. “Nor can we directly control the erosion of perceived value,” another person says. “That’s tied to what our competitors are doing.”

It’s crossed out.

“We’d like to figure out what our viewers really want,” a third person says, “but it’s a huge research project. And the stations are too diverse to decide what data they need.” A heated debate ensues, but ultimately the issue gets crossed off the list.

Next on the list: “Lack of consistent standards.”

“Is that an issue the group can tackle?” you ask.

No one says anything for a few seconds. Finally, someone speaks. “You know, we could conduct interesting research on this question. But we lack a representative group that can decide what research will satisfy us all.”

Lots of heads nod.

Someone says: “If we had that, we could tackle a host of issues – like what our viewers want.”

At this point, someone recaps what has emerged in the last few minutes of the conversation: “We’re saying that the most important issue is the lack of a representative group to decide important industry issues. Isn’t that right?”

Heads nod. Everyone agrees.

Ask everyone in the group to express their feelings about the conversation to this point. Probe for any possible doubts. Again, remind the group that defining the issue correctly is 80 percent of the solution. If you don’t have consensus, ask for further input.

Someone may ask:

“What criteria should we be using to know that we’ve identified the primary issue?”

If the group is still torn between several possible issues, here’s another test. Ask them to imagine that each issue will take exactly the same amount of money to resolve. Put a figure on the table, say $50,000. Then ask the group which would be the best investment? If necessary, split the group into task forces and give them each 45 minutes to discuss and report back to the group. Nine times out of ten, both groups will report back the same conclusion. At that point, move on to Step 5.

Two groups might identify different issues as primary. The key is to make sure that everyone in the group agrees and is committed to resolving the issue. Not superficially, but within the heat of straight talk.

If no agreement is reached on the issue, then ask the group why they’ve reached this impasse. Are certain issues not on the table? Are undiscussibles getting in the way? Are the group conflicts such that productive conversations are impossible? Review our post on Resolving Conflict With Straight Talk for ways to resolve conflicts.

Your group has taken the time to frame the issue clearly. You all agree that it is an issue within your control, and that it is the most important issue that needs to be resolved.

If you have time, shift the focus of the conversation to generating possible solutions. Frame it this way:

“We’ve gone 80 percent of the distance now. We’re only 20 yards short of the goal. We may not agree on a solution to this issue, today. And that’s okay. At a minimum, what we will achieve, provided we stick by the ground rules, is agreement on what we need to do to resolve it. Let me underscore that point. Our goal is to agree either on a solution or on next steps in gathering information. So let’s make that our goal. We will stop once we agree on a solution, or on a series of next steps.”

If you have more than eight people, it can be helpful to break the group into smaller groups to allow ample time for brain-storming. Regardless of how it’s done, ask each individual or group for feedback, and list their ideas on a flipchart. It may be useful to ask someone to serve as a scribe, to keep more thorough notes on each idea as it’s discussed.

We left the conversation with the decision that the central issue was the lack of a set of measurable benchmarks to define success.

At this point, Mike turns to Paul, the CFO, and asks him a question.

“What financial benchmarks do we currently use?”

“We look at our ratio of fixed costs to variable costs. We look at the ratio of costs to revenues. Profit margin, of course, both pre and post tax.”

Sherry speaks. “But aren’t I correct? Won’t our actual profits double if we increase sales by only a third? Yet since our variable costs are high, our profit margin really won’t go up all that much?”

“That’s right,” says Paul.

“So shouldn’t we look at percent increases in actual profits, as opposed to increases in profit margins, as a key benchmark?”

“That’s a good point,” Mike says. “Paul, do you agree?”

“Sure, but we don’t have any industry averages then. We’d only be bench-marking against ourselves.”

“But that’s one of the keys,” says Sherry. “Our goal should be continuous improvement of our business – not to compare ourselves to anyone else. That’s a much more exciting goal for our team, I think.”

“It also means putting the financial data into everyone’s hands, however,” says Paul. “How comfortable are we doing that?”

“I think we have to,” says Mike.

“Even if it means showing our salaries?” says Sally. “How comfortable are you with that?”

“If someone wants to take issue with what I make, let them. It’s healthy.”

The conversation will continue in a task force after the retreat. The team ultimately sets forth clear benchmarks in sales, marketing, production, accounting, and customer service. Mike will institute a free flow of information throughout the company and a bonus program tied to the new benchmarks. Ultimately, Jensen Yachts will become a much stronger company because of its willingness to communicate using the principles of straight talk.

One of our clients, a television station, created a spin-off news show called Cable One. It was a daring idea – a news show on cable aimed at people with a large appetite for local news.

The company hired a team of producers and reporters to start producing this new show. Company executives explained that people working for it would be paid less than people working for the regular news show because this show would reach a smaller audience. The staff would be rewarded with experience gained working in a big television market.

Two years after Cable One was launched, our firm was hired to diagnose the work environment both at the regular news show and at Cable One. Not surprisingly, Cable One scored lowest in the area of rewards and compensation – meaning this was the area of lowest employee satisfaction.

As we analyzed the causes, it didn’t seem at all surprising that Cable One’s pay scales resulted in low levels of satisfaction.

On the face of it, the reason seemed obvious: Cable One and the network news show were both housed in the same building. Cable One personnel kept running into people from the network affiliate who were making twice as much money as they were. It was human nature for Cable One employees to feel dissatisfied.

At the same time, Cable One scored highest in the one area where the affiliate scored lowest. Cable One employees understood their goals and priorities. People at the network affiliate did not.

That was interesting. Our team sat down one day to review the case.

| The task: Our assignment was to identify the key issues and suggest appropriate solutions. We were accustomed to using straight talk, so we first reminded each other of our styles of communicating. Then we tried to define the problem again. |

“As I see it,” one of my colleagues said, “the problem at Cable One is the shared office. Put them in separate locations, and the salary comparisons disappear.”

“But we know from studies that money is not the most important reward,” said another. “I think the problem is the intangible rewards at Cable One. Look at the low score on the question ‘I’m rewarded for innovation.’ That tells me we’ve got a different problem.”

“Okay,” another colleague chimed in, “my interpretation is that Cable One employees are poorly managed. Their average scores across all categories are among the lowest we’ve seen. Look at all the comments scribbled in the margins. That’s pretty unusual. Some talk about management not practicing what they preach; others say they hate working there. I think the problem is the general quality of management.”

“Let’s clarify our assumptions,” one person said.

“For example, I’m assuming that Cable One doesn’t have the resources to undertake major management change. This is a small, start-up operation. Am I right?”

“I think so,” said another colleague. “But let me clarify mine. I don’t think they’re getting enough intangible rewards. They should be taking some pride in this new venture; they should feel excited about coming to work. But I don’t see that happening. The data is inconclusive.”

“And my assumption,” someone else said, “is that the parent company is the root of the problem. We know their management style is old school. They’ve got shareholders on their minds, nothing else. Managers down the line take their cues from the top. That’s my assumption.”

We began listing on a flipchart the data we needed to help us define the problem more clearly.

Data we need:

|

“So if we had all this information, would we be able to agree on a solution?” we asked.

Someone shook his head. “No, I’d still want to know about the parent company’s influence. It may be an undiscussable. But what if all the problems lead back to them?”

“Can you define a missing piece of data that would help you clarify it in your mind?” someone asked.

A colleague walked up to the flip chart and wrote down one more question:

Data we need:

|

We agreed that if we had good data on all four questions, we’d be in a position to re-define the problem more accurately. Our data analyst was shown the questions. Here’s the summary of her report.

We called the team together to talk through her report and decide next steps.

“I assume that the client doesn’t want to pay more money for more surveys,” someone said. “Am I right?”

“I think so,” another person said. “But I sense that we are closer than we think. What if we hypothesize that managers at Cable One are only looking at revenues to measure their success. We know it’s a channel with tiny ratings. Therefore employees aren’t going to derive much satisfaction from that. Everything points to the fact that the same benchmarks are being used for the small station as the big one. Cable One is caught in a Catch 22. We’ve got to shift the way they measure themselves.”

“That fits in with what I’m seeing,” someone else said. “Their employees aren’t getting rewarded, and the reason is that they haven’t got a reasonable scale to measure themselves by. That leaves them only the salaries and ratings and revenues of Big Brother who happens to be living down the hall. I think we’re onto something.”

We also recommended that Cable One stay in the same building. The new rewards system should make them feel very different from Big Brother.

We hope you’ve gained an appreciation for how many issues can be embedded in a single “issue” – and how important it is to tease apart the various strands before solutions are discussed. These five steps will prevent any little snarls from growing into strategic gridlock. There’s real excitement when a group defines an issue to everyone’s satisfaction. If used in conjunction with straight talk, theses steps enable an issue to get framed so that everyone understands it – and the solution lies within reach.

We’ve introduced these tools in dozens of different organizational and corporate settings – and there’s one consistent question we’re asked.

“Can we really do this on our own?”

The answer is: Yes, you can. The group needs to be familiar with these tools, of course. And it helps if you rotate responsibility so that everyone in the group pushes the process forward. When everyone’s committed to straight talk, groups can do amazing things.

“To know that you do not know is best. To pretend to know when you do not know is a disease.” Lao Tzu (6th century BC)

In this exercise, assume you’re in charge of defining a major problem that needs to be solved by your organization. Write down four issues that come to mind in the box below.

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| The most important issue is: |

In the space at the back of the book (or on a separate piece of paper), map all the related issues, using the techniques described in this chapter. If your map include the other issues you listed above, that’s okay.

Of those issues that lie within your organization’s ability to control, which now do you regard as the most important?

| The most important issue is: |

Finally, list some possible solutions to the issue you’ve defined. Ask yourself what information you would need in order to decide the best solution.

Possible solutions: Information we need:

| 1. | |

| 2. | |

| 3. | |

| 4. |

Leading Resources, Inc. is a Sacramento Executive Coaching firm that develops leaders and leading organizations. Subscribe to our leadership development newsletter to download the PDF – “The 6 Trust-Building Habits of Leaders” to learn more about how to build trust with your team.